P-factor: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

< | <page> | ||

<title>P-factor</title> | |||

<revision> | |||

<text xml:space="preserve"> | |||

< | |||

< | |||

{{Short description|Yawing force caused by a rotating propeller}} | {{Short description|Yawing force caused by a rotating propeller}} | ||

{{Distinguish| | {{Distinguish|p-value}} | ||

{{About|the aerodynamic phenomenon|the p factor of psychopathology|p factor (psychopathology)}} | {{About|the aerodynamic phenomenon|the p factor of psychopathology|p factor (psychopathology)}} | ||

[[File:Propeller blade AOA.png|center|thumb|300px|Pitch of blade angle, chord line, angle of attack]] | |||

[[File:Propeller blade AOA versus pitch.png|center|thumb|300px|Propeller blade angle of attack change with pitch change (right) showing asymmetrical loading]] | |||

'''P-factor''', also known as asymmetric blade effect and asymmetric disc effect, is an [[aerodynamic]] phenomenon experienced by a moving [[propeller (aircraft)|propeller]], wherein the propeller's center of [[thrust]] moves off-center at high [[angle of attack]]. This asymmetry exerts a yawing moment, requiring rudder input to maintain directional control. | |||

== | ==Causes== | ||

[[File:Tilted propeller.png|thumb|Change of forces at increasing angle of attack]] | |||

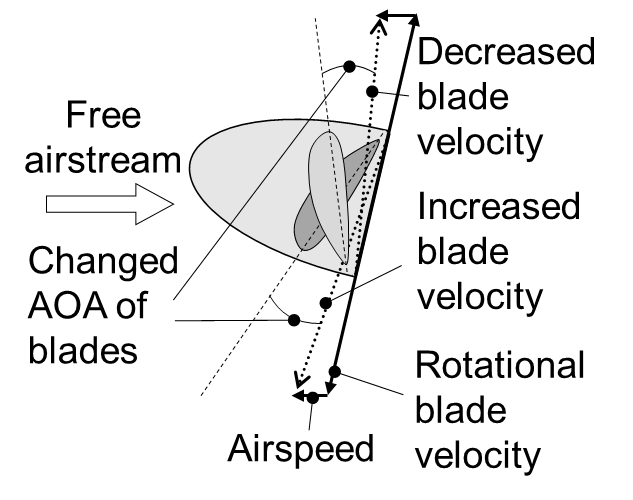

At low airspeeds with nose-high attitude, the propeller disc tilts, causing the down-going blade (typically on the right for clockwise propellers) to move forward with greater speed and angle of attack, producing more thrust. The up-going blade moves backward with lower airspeed and produces less thrust, shifting the thrust center off-axis. | |||

==Effects== | |||

===Single-engine aircraft=== | |||

Clockwise-turning propellers (from pilot view) cause left yaw in climb due to increased thrust on the right side. The effect reverses in descent. Rudder input is needed to maintain coordinated flight. Tailwheel aircraft experience greater P-factor during ground roll due to steeper disc angle. | |||

=== Multi-engine aircraft === | ===Multi-engine aircraft=== | ||

In same-direction twin-engine aircraft, P-factor contributes to determining the [[critical engine]]—the engine whose failure causes more severe yaw. For clockwise props, the left engine is typically critical. Counter-rotating props cancel out P-factor asymmetry. | |||

==Helicopters== | |||

Helicopters experience significant P-factor, especially in forward flight. The advancing blade creates more lift than the retreating blade, requiring cyclic pitch adjustments to maintain stability. Without compensation, the aircraft would roll and pitch undesirably. | |||

== See also == | ==See also== | ||

* [[Propeller walk]] | * [[Propeller walk]] | ||

* [[Dissymmetry of lift]] | * [[Dissymmetry of lift]] | ||

== References == | ==References== | ||

{{ | {{reflist}} | ||

[[Category:Aerodynamics]] | [[Category:Aerodynamics]] | ||

[[Category:Aircraft manufacturing]] | [[Category:Aircraft manufacturing]] | ||

</text> | |||

</revision> | |||

</page> | |||

Revision as of 23:41, 4 April 2025

<page>

<title>P-factor</title> <revision> <text xml:space="preserve">

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

P-factor, also known as asymmetric blade effect and asymmetric disc effect, is an aerodynamic phenomenon experienced by a moving propeller, wherein the propeller's center of thrust moves off-center at high angle of attack. This asymmetry exerts a yawing moment, requiring rudder input to maintain directional control.

Causes

At low airspeeds with nose-high attitude, the propeller disc tilts, causing the down-going blade (typically on the right for clockwise propellers) to move forward with greater speed and angle of attack, producing more thrust. The up-going blade moves backward with lower airspeed and produces less thrust, shifting the thrust center off-axis.

Effects

Single-engine aircraft

Clockwise-turning propellers (from pilot view) cause left yaw in climb due to increased thrust on the right side. The effect reverses in descent. Rudder input is needed to maintain coordinated flight. Tailwheel aircraft experience greater P-factor during ground roll due to steeper disc angle.

Multi-engine aircraft

In same-direction twin-engine aircraft, P-factor contributes to determining the critical engine—the engine whose failure causes more severe yaw. For clockwise props, the left engine is typically critical. Counter-rotating props cancel out P-factor asymmetry.

Helicopters

Helicopters experience significant P-factor, especially in forward flight. The advancing blade creates more lift than the retreating blade, requiring cyclic pitch adjustments to maintain stability. Without compensation, the aircraft would roll and pitch undesirably.

See also

References

</text> </revision>

</page>