Mac (computer)

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

Lua error in Module:Effective_protection_level at line 52: attempt to index field 'TitleBlacklist' (a nil value).

Template:Infobox computing device Mac is a brand of personal computers designed and marketed by Apple since 1984. The name is short for Macintosh (its official name until 1999), a reference to a type of apple called McIntosh. The current product lineup includes the MacBook Air and MacBook Pro laptops, and the iMac, Mac Mini, Mac Studio, and Mac Pro desktops. Macs are currently sold with Apple's UNIX-based macOS operating system, which is not licensed to other manufacturers and exclusively bundled with Mac computers. This operating system replaced Apple's original Macintosh operating system, which has variously been named System, Mac OS, and Classic Mac OS.

Jef Raskin conceived the Macintosh project in 1979, which was usurped and redefined by Apple co-founder Steve Jobs in 1981. The original Macintosh was launched in January 1984, after Apple's "1984" advertisement during Super Bowl XVIII. A series of incrementally improved models followed, sharing the same integrated case design. In 1987, the Macintosh II brought color graphics, but priced as a professional workstation and not a personal computer. Beginning in 1994 with the Power Macintosh, the Mac transitioned from Motorola 68000 series processors to PowerPC. Macintosh clones by other manufacturers were also briefly sold afterwards. The line was refreshed in 1998 with the launch of iMac G3, reinvigorating the line's competitiveness against commodity IBM PC compatibles. Macs transitioned to Intel x86 processors by 2006 along with new sub-product lines MacBook and Mac Pro. Since 2020, Macs have transitioned to Apple silicon chips based on ARM64.

History

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

1979–1996: "Macintosh" era

In the late 1970s, the Apple II became one of the most popular computers, especially in education. After IBM introduced the IBM PC in 1981, its sales surpassed the Apple II. In response, Apple introduced the Lisa in 1983.[1] The Lisa's graphical user interface was inspired by strategically licensed demonstrations of the Xerox Star. Lisa surpassed the Star with intuitive direct manipulation, like the ability to drag and drop files, double-click to launch applications, and move or resize windows by clicking and dragging instead of going through a menu.[2][3] However, hampered by its high price of Template:US$ and lack of available software, the Lisa was commercially unsuccessful.[1]

Parallel to the Lisa's development, a skunkworks team at Apple was working on the Macintosh project. Conceived in 1979 by Jef Raskin, Macintosh was envisioned as an affordable, easy-to-use computer for the masses. Raskin named the computer after his favorite type of apple, the McIntosh. The initial team consisted of Raskin, hardware engineer Burrell Smith, and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. In 1981, Steve Jobs was removed from the Lisa team and joined Macintosh, and was able to gradually take control of the project due to Wozniak's temporary absence after an airplane crash. Under Jobs, the Mac grew to resemble the Lisa, with a mouse and a more intuitive graphical interface, at a quarter of the Lisa's price.[4]

Upon its January 1984 launch, the first Macintosh was described as "revolutionary" by The New York Times.[5] Sales initially met projections, but dropped due to the machine's low performance, single floppy disk drive requiring frequent disk swapping, and initial lack of applications. Author Douglas Adams said of it, "…what I (and I think everybody else who bought the machine in the early days) fell in love with was not the machine itself, which was ridiculously slow and underpowered, but a romantic idea of the machine. And that romantic idea had to sustain me through the realities of actually working on the 128K Mac."[6] Most of the original Macintosh team left Apple, and some followed Jobs to found NeXT after he was forced out by CEO John Sculley.[7] The first Macintosh nevertheless generated enthusiasm among buyers and some developers, who rushed to develop entirely new programs for the platform, including PageMaker, MORE, and Excel.[8] Apple soon released the Macintosh 512K with improved performance and an external floppy drive.[9] The Macintosh is credited with popularizing the graphical user interface,[10] Jobs's fascination with typography gave it an unprecedented variety of fonts and type styles like italics, bold, shadow, and outline.[11] It is the first WYSIWYG computer, and due in large part to PageMaker and Apple's LaserWriter printer, it ignited the desktop publishing market, turning the Macintosh from an early let-down into a notable success.[12] Levy called desktop publishing the Mac's "Trojan horse" in the enterprise market, as colleagues and executives tried these Macs and were seduced into requesting one for themselves. PageMaker creator Paul Brainerd said: "You would see the pattern. A large corporation would buy PageMaker and a couple of Macs to do the company newsletter. The next year you'd come back and there would be thirty Macintoshes. The year after that, three hundred."[13]

In late 1985, Bill Atkinson, one of the few remaining employees to have been on the original Macintosh team, proposed that Apple create a Dynabook, Alan Kay's concept for a tablet computer that stores and organizes knowledge. Sculley rebuffed him, so he adapted the idea into a Mac program, HyperCard, whose cards store any information—text, image, audio, video—with the memex-like ability to semantically link cards together. HyperCard was released in 1987 and bundled with every Macintosh.[14]

In the late 1980s, Jean-Louis Gassée, a Sculley protégé who had succeeded Jobs as head of the Macintosh division, made the Mac more expandable and powerful to appeal to tech enthusiasts and enterprise customers.[15] This strategy led to the successful 1987 release of the Macintosh II, which appealed to power users and gave the lineup momentum. However, Gassée's "no-compromise" approach foiled Apple's first laptop, the Macintosh Portable, which has many uncommon power user features, but is almost as heavy as the original Macintosh at twice its price. Soon after its launch, Gassée was fired.[16]

Since the Mac's debut, Sculley had opposed lowering the company's profit margins, and Macintoshes were priced far above entry-level MS-DOS compatible computers. Steven Levy said that though Macintoshes were superior, the cheapest Mac cost almost twice as much as the cheapest IBM PC compatible.[17][page needed] Sculley also resisted licensing the Mac OS to competing hardware vendors, who could have undercut Apple on pricing and jeopardized its hardware sales, as IBM PC compatibles had done to IBM. These early strategic steps caused the Macintosh to lose its chance at becoming the dominant personal computer platform.[18][19] Though senior management demanded high-margin products, a few employees disobeyed and set out to create a computer that would live up to the original Macintosh's slogan, "[a] computer for the rest of us", which the market clamored for. In a pattern typical of Apple's early era, of skunkworks projects like Macintosh and Macintosh II lacking adoption by upper management who were late to realize the projects' merit, this once-renegade project was actually endorsed by senior management following market pressures. In 1990 came the Macintosh LC and the more affordable Macintosh Classic, the first model under Template:US$. Between 1984 and 1989, Apple had sold one million Macs, and another 10 million over the following five years.[20]

In 1991, the Macintosh Portable was replaced with the smaller and lighter PowerBook 100, the first laptop with a palm rest and trackball in front of the keyboard. The PowerBook brought Template:US$ of revenue within one year, and became a status symbol.[21] By then, the Macintosh represented 10% to 15% of the personal computer market.[22] Fearing a decline in market share, Sculley co-founded the AIM alliance with IBM and Motorola to create a new standardized computing platform, which led to the creation of the PowerPC processor architecture, and the Taligent operating system.[23] In 1992, Apple introduced the Macintosh Performa line, which "grew like ivy" into a disorienting number of barely differentiated models in an attempt to gain market share. This backfired by confusing customers, but the same strategy soon afflicted the PowerBook line.[24] Michael Spindler continued this approach when he succeeded Sculley as CEO in 1993.[25] He oversaw the Mac's transition from Motorola 68000 series to PowerPC and the release of Apple's first PowerPC machine, the well-received Power Macintosh.[26]

Many new Macintoshes suffered from inventory and quality control problems. The 1995 PowerBook 5300 was plagued with quality problems, with several recalls as some units even caught fire. Pessimistic about Apple's future, Spindler repeatedly attempted to sell Apple to other companies, including IBM, Kodak, AT&T, Sun, and Philips. In a last-ditch attempt to fend off Windows, Apple yielded and started a Macintosh clone program, which allowed other manufacturers to make System 7 computers.[26] However, this only cannibalized the sales of Apple's higher-margin machines.[27] Meanwhile, Windows 95 was an instant hit with customers. Apple was struggling financially as its attempts to produce a System 7 successor had all failed with Taligent, Star Trek, and Copland, and its hardware was stagnant. The Mac was no longer competitive, and its sales entered a tailspin.[28] Corporations abandoned Macintosh in droves, replacing it with cheaper and more technically sophisticated Windows NT machines for which far more applications and peripherals existed. Even some Apple loyalists saw no future for the Macintosh.[29] Once the world's second largest computer vendor after IBM, Apple's market share declined precipitously from 9.4% in 1993 to 3.1% in 1997.[30][31] Bill Gates was ready to abandon Microsoft Office for Mac, which would have slashed any remaining business appeal the Mac had. Gil Amelio, Spindler's successor, failed to negotiate a deal with Gates.[32]

In 1996, Spindler was succeeded by Amelio, who searched for an established operating system to acquire or license for the foundation of a new Macintosh operating system. He considered BeOS, Solaris, Windows NT, and NeXT's NeXTSTEP, eventually choosing the last. Apple acquired NeXT on December 20, 1996, returning its co-founder, Steve Jobs.[28][33]

1997–2011: Steve Jobs era

NeXT had developed the mature NeXTSTEP operating system with strong multimedia and Internet capabilities.[34] NeXTSTEP was also popular among programmers, financial firms, and academia for its object-oriented programming tools for rapid application development.[35][36] In an eagerly anticipated speech at the January 1997 Macworld trade show, Steve Jobs previewed Rhapsody, a merger of NeXTSTEP and Mac OS as the foundation of Apple's new operating system strategy.[37] At the time, Jobs only served as advisor, and Amelio was released in July 1997. Jobs was formally appointed interim CEO in September, and permanent CEO in January 2000.[38] To continue turning the company around, Jobs streamlined Apple's operations and began layoffs.[39] He negotiated a deal with Bill Gates in which Microsoft committed to releasing new versions of Office for Mac for five years, investing $150 million in Apple, and settling an ongoing lawsuit in which Apple alleged that Windows had copied the Mac's interface. In exchange, Apple made Internet Explorer the default Mac browser. The deal was closed hours before Jobs announced it at the August 1997 Macworld.[40]

Jobs returned focus to Apple. The Mac lineup had been incomprehensible, with dozens of hard-to-distinguish models. He streamlined it into four quadrants, a laptop and a desktop each for consumers and professionals. Apple also discontinued several Mac accessories, including the StyleWriter printer and the Newton PDA.[41] These changes were meant to refocus Apple's engineering, marketing, and manufacturing efforts so that more care could be dedicated to each product.[42] Jobs also stopped licensing Mac OS to clone manufacturers, which had cost Apple ten times more in lost sales than it received in licensing fees.[43] Jobs made a deal with the largest computer reseller, CompUSA, to carry a store-within-a-store that would better showcase Macs and their software and peripherals. According to Apple, the Mac's share of computer sales in those stores went from 3% to 14%. In November, the online Apple Store launched with built-to-order Mac configurations without a middleman.[38] When Tim Cook was hired as chief operations officer in March 1998, he closed Apple's inefficient factories and outsourced Mac production to Taiwan. Within months, he rolled out a new ERP system and implemented just-in-time manufacturing principles. This practically eliminated Apple's costly unsold inventory, and within one year, Apple had the industry's most efficient inventory turnover.[44]

Jobs's top priority was "to ship a great new product".[45] The first is the iMac G3, an all-in-one computer that was meant to make the Internet intuitive and easy to access. While PCs came in functional beige boxes, Jony Ive gave the iMac a radical and futuristic design, meant to make the product less intimidating. Its oblong case is made of translucent plastic in Bondi blue, later revised with many colors. Ive added a handle on the back to make the computer more approachable. Jobs declared the iMac would be "legacy-free", succeeding ADB and SCSI with an infrared port and cutting-edge USB ports. Though USB had industry backing, it was still absent from most PCs and USB 1.1 was only standardized one month after the iMac's release.[46] He also controversially removed the floppy disk drive and replaced it with a CD drive. The iMac was unveiled in May 1998, and released in August. It was an immediate commercial success and became the fastest-selling computer in Apple's history, with 800,000 units sold before the year ended. Vindicating Jobs on the Internet's appeal to consumers, 32% of iMac buyers had never used a computer before, and 12% were switching from PCs.[47] The iMac reestablished the Mac's reputation as a trendsetter: for the next few years, translucent plastic became the dominant design trend in numerous consumer products.[48]

Apple knew it had lost its chance to compete in the Windows-dominated enterprise market, so it prioritized design and ease of use to make the Mac more appealing to average consumers, and even teens. The "Apple New Product Process" was launched as a more collaborative product development process for the Mac, with concurrent engineering principles. From then, product development was no longer driven primarily by engineering and with design as an afterthought. Instead, Ive and Jobs first defined a new product's "soul", before it was jointly developed by the marketing, engineering, and operations teams.[49] The engineering team was led by the product design group, and Ive's design studio was the dominant voice throughout the development process.[50]

The next two Mac products in 1999, the Power Mac G3 (nicknamed "Blue and White") and the iBook, introduced industrial designs influenced by the iMac, incorporating colorful translucent plastic and carrying handles. The iBook introduced several innovations: a strengthened hinge instead of a mechanical latch to keep it closed, ports on the sides rather than on the back, and the first laptop with built-in Wi-Fi.[51] It became the best selling laptop in the U.S. during the fourth quarter of 1999.[52] The professional-oriented Titanium PowerBook G4 was released in 2001, becoming the lightest and thinnest laptop in its class, and the first laptop with a wide-screen display; it also debuted a magnetic latch that secures the lid elegantly.[53]

The design language of consumer Macs shifted again from colored plastics to white polycarbonate with the introduction of the 2001 Dual USB "Ice" iBook. To increase the iBook's durability, it eliminated doors and handles, and gained a more minimalistic exterior. Ive attempted to go beyond the quadrant with Power Mac G4 Cube, an innovation beyond the computer tower in a professional desktop far smaller than the Power Mac. The Cube failed in the market and was withdrawn from sale after one year. However, Ive considered it beneficial, because it helped Apple gain experience in complex machining and miniaturization.[54]

The development of a successor to the old Mac OS was well underway. Rhapsody had been previewed at WWDC 1997, featuring a Mach kernel and BSD foundations, a virtualization layer for old Mac OS apps (codenamed Blue Box), and an implementation of NeXTSTEP APIs called OpenStep (codenamed Yellow Box). Apple open-sourced the core of Rhapsody as the Darwin operating system. After several developer previews, Apple also introduced the Carbon API, which provided a way for developers to more easily make their apps native to Mac OS X without rewriting them in Yellow Box. Mac OS X was publicly unveiled in January 2000, introducing the modern Aqua graphical user interface, and a far more stable Unix foundation, with memory protection and preemptive multitasking. Blue Box became the Classic environment, and Yellow Box was renamed Cocoa. Following a public beta, the first version of Mac OS X, version 10.0 Cheetah, was released in March 2001.[55]

In 1999, Apple launched its new "digital lifestyle" strategy of which the Mac became a "digital hub" and centerpiece with several new applications. In October 1999, the iMac DV gained FireWire ports, allowing users to connect camcorders and easily create movies with iMovie; the iMac gained a CD burner and iTunes, allowing users to rip CDs, make playlists, and burn them to blank discs. Other applications include iPhoto for organizing and editing photos, and GarageBand for creating and mixing music and other audio. The digital lifestyle strategy entered other markets, with the iTunes Store, iPod, iPhone, iPad, and the 2007 renaming from Apple Computer Inc. to Apple Inc. By January 2007, the iPod was half of Apple's revenues.[56]

New Macs include the white "Sunflower" iMac G4. Ive designed a display to swivel with one finger, so that it "appear[ed] to defy gravity".[57] In 2003, Apple released the aluminum 12-inch and 17-inch PowerBook G4, proclaiming the "Year of the Notebook". With the Microsoft deal expiring, Apple also replaced Internet Explorer with its new browser, Safari.[58] The first Mac Mini was intended to be assembled in the U.S., but domestic manufacturers were slow and had insufficient quality processes, leading Apple to Taiwanese manufacturer Foxconn.[59] The affordably priced Mac Mini desktop was introduced at Macworld 2005, alongside the introduction of the iWork office suite.[60]

Serlet and Tevanian were both initiating the secret project asked by Steve Jobs to propose to Sony executives, in 2001, to sell Mac OS X on Vaio laptops.[61] They showed them a demonstration at a golf party in Hawaii, with the most expensive Vaio laptop they could have acquired.[62] But due to bad timing, Sony refused, arguing their Vaio sales just started to grow after years of difficulties.[63]

Intel transition and "back to the Mac"

With PowerPC chips falling behind in performance, price, and efficiency, Steve Jobs announced in 2005 the Mac transition to Intel processors, because the operating system had been developed for both architectures since the beginning.[64][65] PowerPC apps run using transparent Rosetta emulation,[66] and Windows boots natively using Boot Camp.[67] This transition helped contribute to a few years of growth in Mac sales.[68]

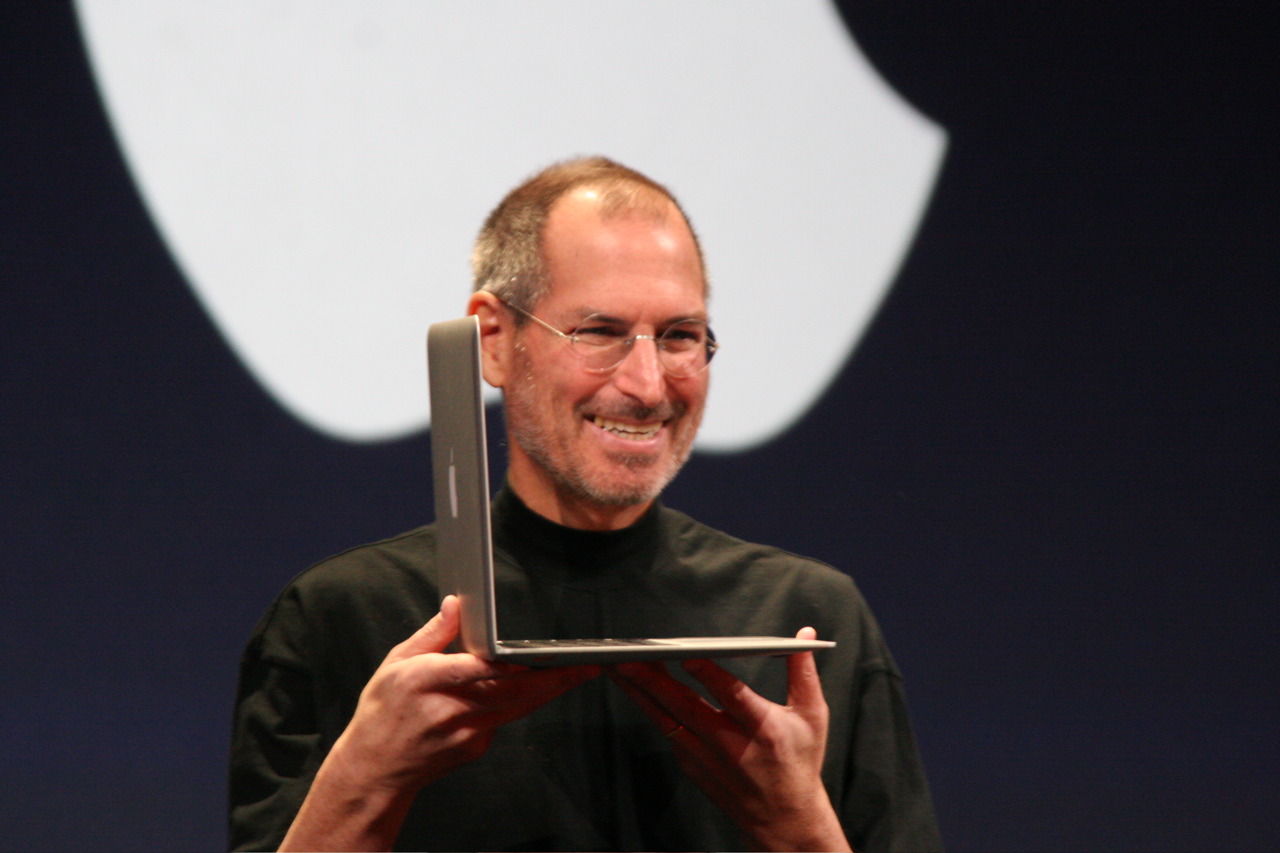

After the iPhone's 2007 release, Apple began a multi-year effort to bring many iPhone innovations "back to the Mac", including multi-touch gesture support, instant wake from sleep, and fast flash storage.[69][70] At Macworld 2008, Jobs introduced the first MacBook Air by taking it out of a manila envelope, touting it as the "world's thinnest notebook".[71] The MacBook Air favors wireless technologies over physical ports, and lacks FireWire, an optical drive, or a replaceable battery. The Remote Disc feature accesses discs in other networked computers.[72] A decade after its launch, journalist Tom Warren wrote that the MacBook Air had "immediately changed the future of laptops", starting the ultrabook trend.[73] OS X Lion added new software features first introduced with the iPad, such as FaceTime, full-screen apps, document autosaving and versioning, and a bundled Mac App Store to replace software install discs with online downloads. It gained support for Retina displays, which had been introduced earlier with the iPhone 4.[74] iPhone-like multi-touch technology was progressively added to all MacBook trackpads, and to desktop Macs through the Magic Mouse, and Magic Trackpad.[75][76] The 2010 MacBook Air added an iPad-inspired standby mode, "instant-on" wake from sleep, and flash memory storage.[77][78]

After criticism by Greenpeace, Apple improved the ecological performance of its products.[79] The 2008 MacBook Air is free of toxic chemicals like mercury, bromide, and PVC, and with smaller packaging.[71] The enclosures of the iMac and unibody MacBook Pro were redesigned with the more recyclable aluminum and glass.[80][81]

On February 24, 2011, the MacBook Pro became the first computer to support Intel's new Thunderbolt connector, with two-way transfer speeds of 10 Gbit/s, and backward compatibility with Mini DisplayPort.[82]

2012–present: Tim Cook era

Due to deteriorating health, Steve Jobs resigned as CEO on August 24, 2011, and Tim Cook was named as his successor.[83] Cook's first keynote address launched iCloud, moving the digital hub from the Mac to the cloud.[84][85] In 2012, the MacBook Pro was refreshed with a Retina display, and the iMac was slimmed and lost its SuperDrive.[86][87]

During Cook's first few years as CEO, Apple fought media criticisms that it could no longer innovate without Jobs.[88] In 2013, Apple introduced a new cylindrical Mac Pro, with marketing chief Phil Schiller exclaiming "Can't innovate anymore, my ass!". The new model had a miniaturized design with a glossy dark gray cylindrical body and internal components organized around a central cooling system. Tech reviewers praised the 2013 Mac Pro for its power and futuristic design;[89][90] however, it was poorly received by professional users, who criticized its lack of upgradability and the removal of expansion slots.[91][92]

The iMac was refreshed with a 5K Retina display in 2014, making it the highest-resolution all-in-one desktop computer.[93] The MacBook was reintroduced in 2015, with a completely redesigned aluminum unibody chassis, a 12-inch Retina display, a fanless low-power Intel Core M processor, a much smaller logic board, a new Butterfly keyboard, a single USB-C port, and a solid-state Force Touch trackpad with pressure sensitivity. It was praised for its portability, but criticized for its lack of performance, the need to use adapters to use most USB peripherals, and a high starting price of Template:US$.[94] In 2015, Apple started a service program to address a widespread GPU defect in the 15-inch 2011 MacBook Pro, which could cause graphical artifacts or prevent the machine from functioning entirely.[95]

Neglect of professional users

The Touch Bar MacBook Pro was released in October 2016. It was the thinnest MacBook Pro ever made, replaced all ports with four Thunderbolt 3 (USB-C) ports, gained a thinner "Butterfly" keyboard, and replaced function keys with the Touch Bar. The Touch Bar was criticized for making it harder to use the function keys by feel, as it offered no tactile feedback. Many users were also frustrated by the need to buy dongles, particularly professional users who relied on traditional USB-A devices, SD cards, and HDMI for video output.[96][97] A few months after its release, users reported a problem with stuck keys and letters being skipped or repeated. iFixit attributed this to the ingress of dust or food crumbs under the keys, jamming them. Since the Butterfly keyboard was riveted into the laptop's case, it could only be serviced at an Apple Store or authorized service center.[98][99][100] Apple settled a $50m class-action lawsuit over these keyboards in 2022.[101][102] These same models were afflicted by "flexgate": when users closed and opened the machine, they would risk progressively damaging the cable responsible for the display backlight, which was too short. The $6 cable was soldered to the screen, requiring a $700 repair.[103][104]

Senior Vice President of Industrial Design Jony Ive continued to guide product designs towards simplicity and minimalism.[105] Critics argued that he had begun to prioritize form over function, and was excessively focused on product thinness. His role in the decisions to switch to fragile Butterfly keyboards, to make the Mac Pro non-expandable, and to remove USB-A, HDMI and the SD card slot from the MacBook Pro were criticized.[106][107][108]

The long-standing keyboard issue on MacBook Pros, Apple's abandonment of the Aperture professional photography app, and the lack of Mac Pro upgrades led to declining sales and a widespread belief that Apple was no longer committed to professional users.[109][110][111][112] After several years without any significant updates to the Mac Pro, Apple executives admitted in 2017 that the 2013 Mac Pro had not met expectations, and said that the company had designed themselves into a "thermal corner", preventing them from releasing a planned dual-GPU successor.[113] Apple also unveiled their future product roadmap for professional products, including plans for an iMac Pro as a stopgap and an expandable Mac Pro to be released later.[114][115] The iMac Pro was revealed at WWDC 2017, featuring updated Intel Xeon W processors and Radeon Pro Vega graphics.[116]

In 2018, Apple released a redesigned MacBook Air with a Retina display, Butterfly keyboard, Force Touch trackpad, and Thunderbolt 3 USB-C ports.[117][118] The Butterfly keyboard went through three revisions, incorporating silicone gaskets in the key mechanism to prevent keys from being jammed by dust or other particles. However, many users continued to experience reliability issues with these keyboards,[119] leading Apple to launch a program to repair affected keyboards free of charge.[120] Higher-end models of the 15-inch 2018 MacBook Pro faced another issue where the Core i9 processor reached unusually high temperatures, resulting in reduced CPU performance from thermal throttling. Apple issued a patch to address this issue via a macOS supplemental update, blaming a "missing digital key" in the thermal management firmware.[121]

The 2019 16-inch MacBook Pro and 2020 MacBook Air replaced the unreliable Butterfly keyboard with a redesigned scissor-switch Magic Keyboard. On the MacBook Pros, the Touch Bar and Touch ID were made standard, and the Esc key was detached from the Touch Bar and returned to being a physical key.[122] At WWDC 2019, Apple unveiled a new Mac Pro with a larger case design that allows for hardware expandability, and introduced a new expansion module system (MPX) for modules such as the Afterburner card for faster video encoding.[123][124] Almost every part of the new Mac Pro is user-replaceable, with iFixit praising its high user-repairability.[125] It received positive reviews, with reviewers praising its power, modularity, quiet cooling, and Apple's increased focus on professional workflows.[126][127]

Apple silicon transition

In April 2018, Bloomberg reported Apple's plan to replace Intel chips with ARM processors similar to those in its phones, causing Intel's shares to drop by 9.2%.[128] The Verge commented on the rumors, that such a decision made sense, as Intel was failing to make significant improvements to its processors, and could not compete with ARM chips on battery life.[129][130]

At WWDC 2020, Tim Cook announced that the Mac would be transitioning to Apple silicon chips, built upon an ARM architecture, over a two-year timeline.[131] The Rosetta 2 translation layer was also introduced, enabling Apple silicon Macs to run Intel apps.[132] On November 10, 2020, Apple announced their first system-on-a-chip designed for the Mac, the Apple M1, and a series of Macs that would ship with the M1: the MacBook Air, Mac Mini, and the 13-inch MacBook Pro.[133] These new Macs received highly positive reviews, with reviewers highlighting significant improvements in battery life, performance, and heat management compared to previous generations.[134][135][136]

The iMac Pro was discontinued on March 6, 2021.[137] On April 20, 2021, a new 24-inch iMac was revealed, featuring the M1 chip, seven new colors, thinner white bezels, a higher-resolution 1080p webcam, and an enclosure made entirely from recycled aluminum.[138][139]

On October 18, 2021, Apple announced new 14-inch and 16-inch MacBook Pros, featuring the more powerful M1 Pro and M1 Max chips, a bezel-less mini-LED 120 Hz ProMotion display, and the return of MagSafe and HDMI ports, and the SD card slot.[140][141][142]

On March 8, 2022, the Mac Studio was unveiled, also featuring the M1 Max chip and the new M1 Ultra chip in a similar form factor to the Mac Mini. It drew highly positive reviews for its flexibility and wide range of available ports.[143] Its performance was deemed "impressive", beating the highest-end Mac Pro with a 28-core Intel Xeon chip, while being significantly more power efficient and compact.[144] It was introduced alongside the Studio Display, meant to replace the 27-inch iMac, which was discontinued on the same day.[145]

Post-Apple silicon transition

At WWDC 2022, Apple announced an updated MacBook Air based on a new M2 chip. It incorporates several changes from the 14-inch MacBook Pro, such as a flat, slab-shaped design, full-sized function keys, MagSafe charging, and a Liquid Retina display, with rounded corners and a display cutout incorporating a 1080p webcam.[146]

The Mac Studio with M2 Max and M2 Ultra chips and the Mac Pro with M2 Ultra chip was unveiled at WWDC 2023, and the Intel-based Mac Pro was discontinued on the same day, completing the Mac transition to Apple silicon chips.[147] The Mac Studio was received positively as a modest upgrade over the previous generation, albeit similarly priced PCs could be equipped with faster GPUs.[148] However, the Apple silicon-based Mac Pro was criticized for several regressions, including memory capacity and a complete lack of CPU or GPU expansion options.[147][149] A 15-inch MacBook Air was also introduced, and is the largest display included on a consumer-level Apple laptop.[150]

The MacBook Pro was updated on October 30, 2023, with updated M3 Pro and M3 Max chips using a 3 nm process node, as well as the standard M3 chip in a refreshed iMac and a new base model MacBook Pro.[151] Reviewers lamented the base memory configuration of 8 GB on the standard M3 MacBook Pro.[152] In March 2024, the MacBook Air was also updated to include the M3 chip.[153] In October 2024, several Macs were announced with the M4 series of chips, including the iMac, a redesigned Mac Mini, and the MacBook Pro; all of which included 16 GB of memory as standard. The MacBook Air was also upgraded with 16 GB for the same price.[154]

Current Mac models

| Release date | Model | Processor |

|---|---|---|

| June 13, 2023 | Mac Pro (2023) | Apple M2 Ultra |

| November 8, 2024 | iMac (24-inch, 2024) | Apple M4 |

| Mac Mini (2024) | Apple M4 or M4 Pro | |

| MacBook Pro (14-inch, 2024) | Apple M4, M4 Pro or M4 Max | |

| MacBook Pro (16-inch, 2024) | Apple M4 Pro or M4 Max | |

| March 12, 2025 | MacBook Air (13-inch, M4, 2025) | Apple M4 |

| MacBook Air (15-inch, M4, 2025) | ||

| Mac Studio (2025) | Apple M4 Max or M3 Ultra |

Marketing

The original Macintosh was marketed at Super Bowl XVIII with the highly acclaimed "1984" ad, directed by Ridley Scott. The ad alluded to George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, and symbolized Apple's desire to "rescue" humanity from the conformity of computer industry giant IBM.[157][158][159] The ad is now considered a "watershed event" and a "masterpiece."[160][161] Before the Macintosh, high-tech marketing catered to industry insiders rather than consumers, so journalists covered technology like the "steel or automobiles" industries, with articles written for a highly technical audience.[162][163] The Macintosh launch event pioneered event marketing techniques that have since become "widely emulated" in Silicon Valley, by creating a mystique about the product and giving an inside look into its creation.[164] Apple took a new "multiple exclusives" approach regarding the press, giving "over one hundred interviews to journalists that lasted over six hours apiece", and introduced a new "Test Drive a Macintosh" campaign.[165][166]

Apple's brand, which established a "heartfelt connection with consumers", is cited as one of the keys to the Mac's success.[167] After Steve Jobs's return to the company, he launched the Think different ad campaign, positioning the Mac as the best computer for "creative people who believe that one person can change the world".[168] The campaign featured black-and-white photographs of luminaries like Albert Einstein, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr., with Jobs saying: "if they ever used a computer, it would have been a Mac".[169][170] The ad campaign was critically acclaimed and won several awards, including a Primetime Emmy.[171] In the 2000s, Apple continued to use successful marketing campaigns to promote the Mac line, including the Switch and Get a Mac campaigns.[172][173]

Apple's focus on design and build quality has helped establish the Mac as a high-end, premium brand. The company's emphasis on creating iconic and visually appealing designs for its computers has given them a "human face" and made them stand out in a crowded market.[174] Apple has long made product placements in high-profile movies and television shows to showcase Mac computers, like Mission: Impossible, Legally Blonde, and Sex and the City.[175] Apple is known for not allowing producers to show villains using Apple products.[176] Its own shows produced for the Apple TV+ streaming service feature prominent use of MacBooks.[177]

The Mac is known for its highly loyal customer base. In 2022, the American Customer Satisfaction Index gave the Mac the highest customer satisfaction score of any personal computer, at 82 out of 100.[178] In that year, Apple was the fourth largest vendor of personal computers, with a market share of 8.9%.[179]

Hardware

Apple outsources the production of its hardware to Asian manufacturers like Foxconn and Pegatron.[180][181] As a highly vertically integrated company developing its own operating system and chips, it has tight control over all aspects of its products and deep integration between hardware and software.[182]

All Macs in production use ARM-based Apple silicon processors and have been praised for their performance and power efficiency.[183] They can run Intel apps through the Rosetta 2 translation layer, and iOS and iPadOS apps distributed via the App Store.[184] These Mac models come equipped with high-speed Thunderbolt 4 or USB 4 connectivity, with speeds up to 40 Gbit/s.[185][186] Apple silicon Macs have custom integrated graphics rather than graphics cards.[187] MacBooks are recharged with either USB-C or MagSafe connectors, depending on the model.[188]

Apple sells accessories for the Mac, including the Studio Display and Pro Display XDR external monitors,[189] the AirPods line of wireless headphones,[190] and keyboards and mice such as the Magic Keyboard, Magic Trackpad, and Magic Mouse.[191]

Software

<templatestyles src="Module:Hatnote/styles.css"></templatestyles>

Template:MacOS sidebar Macs run the macOS operating system, which is the second most widely used desktop OS according to StatCounter.[192] Macs can also run Windows, Linux, or other operating systems through virtualization, emulation, or multi-booting.[193][194][195]

macOS is the successor of the classic Mac OS, which had nine releases between 1984 and 1999. The last version of classic Mac OS, Mac OS 9, was introduced in 1999. Mac OS 9 was succeeded by Mac OS X in 2001.[196] Over the years, Mac OS X was rebranded first to OS X and later to macOS.[197]

macOS is a derivative of NextSTEP and FreeBSD. It uses the XNU kernel, and the core of macOS has been open-sourced as the Darwin operating system.[198] macOS features the Aqua user interface, the Cocoa set of frameworks, and the Objective-C and Swift programming languages.[199] Macs are deeply integrated with other Apple devices, including the iPhone and iPad, through Continuity features like Handoff, Sidecar, Universal Control, and Universal Clipboard.[200]

The first version of Mac OS X, version 10.0, was released in March 2001.[201] Subsequent releases introduced major changes and features to the operating system. 10.4 Tiger added Spotlight search;[202] 10.6 Snow Leopard brought refinements, stability, and full 64-bit support;[203] 10.7 Lion introduced many iPad-inspired features;[66] 10.10 Yosemite introduced a complete user interface revamp, replacing skeuomorphic designs with iOS 7-esque flat designs;[204] 10.12 Sierra added the Siri voice assistant and Apple File System (APFS) support;[205] 10.14 Mojave added a dark user interface mode;[206] 10.15 Catalina dropped support for 32-bit apps;[207] 11 Big Sur introduced an iOS-inspired redesign of the user interface,[208] 12 Monterey added the Shortcuts app, Low Power Mode, and AirPlay to Mac;[209] and 13 Ventura added Stage Manager, Continuity Camera, and passkeys.[210]

The Mac has a variety of apps available, including cross-platform apps like Google Chrome, Microsoft Office, Adobe Creative Cloud, Mathematica, Visual Studio Code, Ableton Live, and Cinema 4D.[211] Apple has also developed several apps for the Mac, including Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, iWork, GarageBand, and iMovie.[212] A large amount of open-source software applications run natively on macOS, such as LibreOffice, VLC, and GIMP,[213] and command-line programs, which can be installed through Macports and Homebrew.[214] Many applications for Linux or BSD also run on macOS, often using X11.[215] Apple's official integrated development environment (IDE) is Xcode, allowing developers to create apps for the Mac and other Apple platforms.[216]

The latest release of macOS is macOS 15 Sequoia, released on September 16, 2024.[217]

Timeline

Template:Timeline of Mac model families

References

Bibliography

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

Further reading

<templatestyles src="Refbegin/styles.css" />

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

The Original Macintosh. Andy Hertzfeld. folklore.org. Retrieved April 24, 2006 from link

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

1984: The First Macs. Dan Knight. Low End Mac. Retrieved April 24, 2006 from link

- Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

A History of Apple's Operating Systems. Amit Singh. Retrieved April 24, 2006 from link

External links

<templatestyles src="Module:Side box/styles.css"></templatestyles><templatestyles src="Sister project/styles.css"></templatestyles>

Template:Apple Inc. Template:Apple hardware before 1998 Template:Apple hardware since 1998 Template:Apple operating systems Template:Classic Mac OS Template:MacOS

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Linzmayer 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 90–101, 135–138.

- ↑ Malone 1999, pp. 232–244.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 85–88, 92–94. Wozniak plane crash: p. 15.

- ↑ Sandberg-Diment 1984, p. C3.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 185–187, 193–196.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 201–203.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 198, 218–220.

- ↑ Levy 2000, p. 200.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, p. 103.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Levy 2000, p. 211, 220–222.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 239–247.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 226–234.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Levy 2000.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 222–225.

- ↑ Malone 1999, p. 416.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 227–234.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Levy 2000, pp. 281, 298.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Malone 1999, pp. 439–440.

- ↑ Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 90, 190.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Linzmayer 2004, pp. 233–237.

- ↑ Clone wars: When the licensed copies were better than Apple's own Macs. Christopher Phin. (October 26, 2015) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 190–197.

- ↑ Malone 1999, pp. 523–527.

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Malone 1999, p. 518.

- ↑ Malone 1999, p. 521.

- ↑ The Deep History of Your Apps: Steve Jobs, NeXTSTEP, and Early Object-Oriented Programming. Hansen Hsu. (March 15, 2016) Retrieved November 16, 2022 from Computer History Museum

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 207–213.

- ↑ Malone 1999, pp. 529, 554.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Linzmayer 2004, pp. 289–298.

- ↑ Isaacson 2011, p. 336-339, 359.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 288–291.

- ↑ Isaacson 2011, p. 336-339.

- ↑ Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, p. 254-256, 291-292.

- ↑ Mickle 2022, pp. 93–99.

- ↑ Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 224.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 113–134, 140–141.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 113–134.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, p. 149.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 135–143.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, p. 149, 200.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 143–149.

- ↑ iBook takes top slot in US retail sales. Tony Smith. (November 23, 1999) Retrieved December 13, 2022 from The Register

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 153–158.

- ↑ Singh 2006, pp. 10–15, 27–36.

- ↑ Isaacson 2011, pp. 378–410.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 187–191.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 301–302.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 203–210.

- ↑ Kahney 2013, pp. 187–191, 203–210.

- ↑ Steve Jobs wanted Sony VAIOs to run OS X. Aaron Souppouris. (2014-02-05) Retrieved 2024-05-14 from The Verge

- ↑ sony-turned-down-offer-from-steve-jobs-to-run-mac-os-on-vaio-laptops-says-ex-president/. (February 5, 2014) Retrieved May 14, 2024 from link

- ↑ The tales of Steve Jobs & Japan #02: casual friendship with Sony | Steve Jobs and Japan | nobi.com (EN). (2014-02-05) Retrieved 2024-05-14 from nobi.com

- ↑ Schlender & Tetzeli 2015, pp. 373–374.

- ↑ Chip Story: The Intel Mac FAQ, 2006 edition. Jason Snell. (January 11, 2006) Retrieved December 15, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Mac OS X 10.7 Lion: the Ars Technica review. John Siracusa. (July 20, 2011) Retrieved December 4, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Apple unveils official support for booting Windows. Clint Ecker. (April 5, 2006) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Making sense of Mac market share figures. Jacqui Cheng. (February 24, 2009) Retrieved December 15, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Thin is in: Ars Technica reviews the MacBook Air. Jacqui Cheng. (February 4, 2008) Retrieved December 4, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Steve Jobs changed the future of laptops 10 years ago today. Tom Warren. (January 15, 2018) Retrieved December 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Mac OS X Lion gets lion's share of new features from the iPad. Richard Trenholm. (February 24, 2011) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Apple's new 11.6-in. MacBook Air: Don't call it a netbook. Ken Mingis. (October 28, 2010) Retrieved December 4, 2022 from Computerworld

- ↑ The future of notebooks: Ars reviews the 11" MacBook Air. Chris Foresman. (November 3, 2010) Retrieved December 4, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ How Apple and Greenpeace made peace. Candace Lombardi. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from CNET

- ↑ The New MacBook's Green Credentials. Joe Hutsko. (November 17, 2008) Retrieved December 1, 2022 from The New York Times

- ↑ Why you should pay more attention to Apple's green slide. Jonny Evans. (May 25, 2022) Retrieved December 1, 2022 from Computerworld

- ↑ What you need to know about Thunderbolt. (February 24, 2011) Retrieved December 15, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ iCloud Is a Bigger Deal Than You Think: It's the Future of Computing. Mat Honan. (October 12, 2011) Retrieved February 10, 2023 from Gizmodo

- ↑ Mickle 2022, pp. 5–11.

- ↑ WWDC 2012: Retina Display reaches MacBook Pro. Jonny Evans. (June 11, 2012) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Computerworld

- ↑ A First Look at the 2012 21.5-inch iMac, And How It Compares To Generations Past. Darrell Etherington. (November 30, 2012) Retrieved September 30, 2022 from TechCrunch

- ↑ Mickle 2022, pp. 10–11, 144–148.

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ A pro with serious workstation needs reviews Apple's 2013 Mac Pro. Dave Girard. (January 28, 2014) Retrieved November 15, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Mickle 2022, p. 163, "When [the Mac Pro] launched months later, customer interest fell short of what Apple had hoped [...] orders plummeted, and the company wound up slashing production. It became known inside the company as "the failed trash can.".

- ↑ Why Apple's Mac Pro 'trash can' was a colossal failure. Michelle Yan Huang. Retrieved November 21, 2022 from Business Insider

- ↑ iMac with Retina display review: best in class, but not everybody needs one. (October 22, 2014) Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Engadget

- ↑ 12-inch MacBook review. Dieter Bohn. (April 9, 2015) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Users Reporting Widespread GPU Issues with 2011 MacBook Pros. Josh Centers. (December 19, 2013) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from TidBITS

- ↑ MacBook Pro with Touch Bar review: a touch of the future. Miranda Nielsen. (November 14, 2016) Vox Media. Retrieved March 16, 2021 from The Verge

- ↑ MacBook Pro review (2016): A step forward and a step back. Dana Wollman. (November 14, 2016) Engadget. Retrieved March 16, 2021 from link

- ↑ Anatomy of a Butterfly (Keyboard)—Teardown Style | iFixit News. (October 4, 2022) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from iFixit

- ↑ Appl Still Hasn't Fixd Its MacBook Kyboad Problm. Joanna Stern. (March 27, 2019) Retrieved March 16, 2021 from The Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Apple Engineers Its Own Downfall With the Macbook Pro Keyboard. (October 4, 2022) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from iFixit

- ↑ Judge approves Apple's massive MacBook keyboard lawsuit payout. David Price. (November 30, 2022) Retrieved December 20, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ "Flexgate" might be Apple's next MacBook Pro problem. Chaim Gartenberg. (January 22, 2019) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple quietly addressed 'Flexgate' issue with MacBook Pro redesign. Jon Porter. (March 5, 2019) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Why Apple's Mac Pro 'trash can' was a colossal failure. Michelle Yan Huang. Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Business Insider

- ↑ Mac sales are down 13% year-on-year, though things may be better than they seem. Ben Lovejoy. (August 1, 2018) Retrieved September 30, 2022 from 9to5Mac

- ↑ The MacBook Pro is a lie. Vlad Savov. (November 7, 2016) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ The new MacBook Pro isn't just a laptop, it's a strategy shift. Michael Simon. (November 1, 2016) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ Why 2016 is such a terrible year for the Mac. Jason Snell. (November 2, 2016) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ Apple admits the Mac Pro was a mess. Jacob Kastrenakes. (April 4, 2017) Retrieved December 13, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple Says It Is "Completely Rethinking" The Mac Pro. John Paczkowski. (April 4, 2017) Retrieved October 9, 2022 from BuzzFeed News

- ↑ Apple admits the Mac Pro was a mess. Jacob Kastrenakes. (April 4, 2017) Retrieved October 9, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple announces new iMac Pro with up to 18-core processor, 5K display. Nick Statt. (June 5, 2017) Retrieved December 13, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ The first reviews of Apple's new MacBook Pro are out – here's what critics had to say. Sean Wolfe. (July 18, 2018) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Business Insider

- ↑ Apple's keyboard 'material' changes on the new MacBook Pro are minor at best. Dieter Bohn. (May 24, 2019) Retrieved December 16, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple offers free keyboard replacement program for MacBook, MacBook Pro, refreshes MacBook Pro lineup. Larry Dignan. (May 29, 2019) Retrieved September 30, 2022 from ZDNet

- ↑ New MacBook Pro review: the heat is on. Dieter Bohn. (July 25, 2018) Retrieved February 10, 2023 from The Verge

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Apple announces all-new redesigned Mac Pro, starting at $5,999. Vlad Savov. (June 3, 2019) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ The Thermodynamics Behind the Mac Pro, the Hypercar of Computers. (December 10, 2019) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Popular Mechanics

- ↑ iFixit Mac Pro teardown. (December 17, 2019) Retrieved March 16, 2021 from iFixit

- ↑ Mac Pro review: power, if you can use it. Nilay Patel. (March 2, 2020) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple Mac Pro (2019): Premium hardware for serious professionals. Retrieved October 4, 2022 from ZDNet

- ↑ Apple Plans to Use Its Own Chips in Macs From 2020, Replacing Intel. (April 2, 2018) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Bloomberg

- ↑ Chips are down: Apple to stop using Intel processors in Macs, reports say. (April 3, 2018) Retrieved March 26, 2021 from The Guardian

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Apple is switching Macs to its own processors starting later this year. Tom Warren. (June 22, 2020) Retrieved June 23, 2020 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple Silicon at WWDC 2020: Everything you need to know. Retrieved November 7, 2022 from ZDNet

- ↑ Apple details new MacBook Air, MacBook Pro and Mac Mini, all powered by in-house silicon chips. Rishi Iyengar. (November 10, 2020) Retrieved November 13, 2020 from CNN

- ↑ The Verge M1 MBP review. Nilay Patel. (November 17, 2020) Retrieved March 16, 2021 from The Verge

- ↑ Tom's Guide M1 MBP review. (November 9, 2021) Retrieved March 16, 2021 from Tom's Guide

- ↑ Apple MacBook Air (M1, 2020) review. Matt Hanson last updated. (November 18, 2021) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from TechRadar

- ↑ Apple discontinues the iMac Pro. Mikael Markander. (March 8, 2021) Retrieved December 13, 2022 from Macworld

- ↑ Apple's new iMac is fun and functional. Monica Chin. (May 18, 2021) Retrieved November 7, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Apple announces new 14-inch MacBook Pro with a notch. Mitchell Clark. (October 18, 2021) Retrieved December 13, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple MacBook Pro 14-inch (2021) review. (30 September 2022) Retrieved 30 March 2024 from Tom's Guide

- ↑ Apple MacBook Pro (M1 Pro) In-Depth Review: Perfect Pro Laptop. (11 November 2021) Retrieved 30 March 2024 from Digital Trends

- ↑ Apple's new strategy is to give – not tell – users what they want. Jon Porter. (March 9, 2022) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Review: The Mac Studio shows us exactly why Apple left Intel behind. Andrew Cunningham. (March 17, 2022) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ The 27-inch iMac has been discontinued. Victoria Song. (March 8, 2022) Retrieved March 22, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple MacBook Air M2 (2022) review: all-new Air. Dan Seifert. (July 14, 2022) Retrieved November 15, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Which professionals is the Mac Pro for? We couldn't find them. Monica Chin. (June 27, 2023) Retrieved July 18, 2023 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple Mac Studio (M2 Ultra) review: Pro Performance in a compact package. (2023-10-04) Retrieved 2024-01-02 from TechRadar

- ↑ Mac renaissance: How Apple's chip transition yielded such an oddly configured Mac Pro. Retrieved July 18, 2023 from ZDNET

- ↑ Apple MacBook Air 15-inch review: A bigger screen makes a surprising difference. (2023-06-12) Retrieved 2024-03-30 from Engadget

- ↑ Here's where you can preorder Apple's new M3-powered Macs. Antonio G. Di Benedetto. (2023-10-31) Retrieved 2024-03-30 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple MacBook Pro 14 (2023) review: entry-level enigma. Victoria Song. (2023-11-06) Retrieved 2024-01-02 from The Verge

- ↑ Review: Apple's efficient M3 MacBook Airs are just about as good as laptops get. Andrew Cunningham. (2024-03-07) Retrieved 2024-03-30 from Ars Technica

- ↑ The MacBook Air's free RAM upgrade was sneakily the best announcement during Apple's Mac event. Cesar Cadenas. (2024-08-30) Retrieved 2024-03-30 from ZDNet

- ↑ Apple – Support – Technical Specifications. Retrieved November 16, 2022 from support.apple.com

- ↑ Apple – Support – Technical Specifications. Retrieved November 16, 2022 from support.apple.com

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Hertzfeld 2004, pp. 181–183.

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Evelyn Richards on Apple's Influence on Technology Journalism and PR. Wendy Marinaccio. (June 22, 2000) Stanford University. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Making the Macintosh: Technology and Culture in Silicon Valley

- ↑ Evelyn Richards on High-Tech Journalism in the 1980s. Wendy Marinaccio. (June 22, 2000) Stanford University. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from link

- ↑ The Macintosh Marketing Campaign. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang. (July 14, 2000) Stanford University. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Making the Macintosh: Technology and Culture in Silicon Valley

- ↑ Andy Cunningham on the Influence of the Macintosh Launch. Wendy Marinaccio. (14 July 2000) Stanford University. Retrieved April 19, 2015 from Making the Macintosh: Technology and Culture in Silicon Valley

- ↑ Andy Cunningham on the Macintosh Introduction. Wendy Marinaccio. (14 July 2000) Stanford University. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from link

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Einstein would have used a Mac. Lennon, too.. John Paczkowski. (August 28, 2010) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ The Real Story Behind Apple's 'Think Different' Campaign. Rob Siltanen. (December 14, 2011) Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Forbes

- ↑ TBWA Think Different Ad wins Emmy. (September 1, 1998) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Campaign

- ↑ The 'Get a Mac' campaign was instrumental in shaping Apple's reputation with consumers. (February 7, 2020) Retrieved October 15, 2022 from iMore

- ↑ Steve Jobs made 3 AM phone calls to argue about Apple ads. (May 7, 2018) Retrieved February 10, 2023 from Business Insider

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).; Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ 12 Excellent Examples Of How Apple Product Placements Rule Hollywood. Laura Stampler. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Business Insider

- ↑ Apple tells moviemakers that villains can't use iPhones, Rian Johnson says. Jon Brodkin. (February 26, 2020) Retrieved September 29, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Hundreds of iPhones Are in 'Ted Lasso.' They're More Strategic Than You Think.. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from The Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Apple tops the PC satisfaction index again. But Samsung has narrowed the gap. Retrieved September 29, 2022 from ZDNet

- ↑ Mac market bucks trend with continued growth while PC shipments slow. José Adorno. (April 11, 2022) Retrieved September 29, 2022 from 9to5Mac

- ↑ Foxconn, Pegatron & other Apple suppliers reportedly under pressure as Apple squeezes margins. Ben Lovejoy. (July 5, 2016) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from 9to5Mac

- ↑ Mickle 2022, pages 97-99, 237-239.

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ Apple Silicon: The Complete Guide. Retrieved November 18, 2022 from MacRumors

- ↑ Mac Mini and Apple Silicon M1 review: Not so crazy after all. Samuel Axon. (November 19, 2020) Retrieved November 18, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Apple brings USB 4 to its Mac line as it unveils computers with its own M1 chips. Stephen Shankland. Retrieved December 5, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ Apple Intros First Three 'Apple Silicon' Macs: Late 2020 MacBook Air, 13-Inch MacBook Pro, & Mac Mini. Ryan Smith. Retrieved November 15, 2022 from AnandTech

- ↑ Apple has built its own Mac graphics processors. Jonny Evans. (July 7, 2020) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from Computerworld

- ↑ Apple brings MagSafe 3 to the new MacBook Pro. Richard Lawler. (October 18, 2021) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple Studio Display vs. Pro Display XDR: The Same, Yet Not. Lori Grunin. Retrieved December 5, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ Here's how the new AirPods Pro compare to the rest of Apple's AirPods lineup. Sheena Vasani. (September 10, 2022) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Apple's New Two-Toned Magic Keyboard With Touch ID, Trackpad and Mouse Are Now Available. Jared DiPane. Retrieved December 5, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ Desktop Operating System Market Share Worldwide. Retrieved May 6, 2023 from StatCounter Global Stats

- ↑ Windows or Mac? Apple Says Both. (April 6, 2006) Retrieved May 6, 2023 from The New York Times

- ↑ How to install Linux and breathe new life into an older Mac. Retrieved May 6, 2023 from Macworld

- ↑ Best virtual machine software for Mac 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023 from Macworld

- ↑ Looking back at the Mac OS (pictures). James Martin. (January 24, 2014) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from CNET

- ↑ It's been 20 years since the launch of Mac OS X. Samuel Axon. (March 24, 2021) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Singh 2006, pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Lua error: bad argument #1 to "get" (not a valid title).

- ↑ How Universal Control on macOS Monterey works. Dieter Bohn. (June 8, 2021) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ Mac OS X 10.0. John Siracusa. (April 2, 2001) Retrieved November 15, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger. John Siracusa. (April 28, 2005) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard: the Ars Technica review. John Siracusa. (September 1, 2009) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ A Look At OS X Yosemite And iOS 8.1. Brandon Chester. (October 27, 2014) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from AnandTech

- ↑ macOS 10.12 Sierra: The Ars Technica review. Andrew Cunningham. (September 20, 2016) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ macOS 10.14 Mojave: The Ars Technica review. Andrew Cunningham. (September 24, 2018) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ macOS 10.15 Catalina: The Ars Technica review. (October 7, 2019) Retrieved May 7, 2023 from Ars Technica

- ↑ macOS 11.0 Big Sur: The Ars Technica review. Andrew Cunningham. (November 12, 2020) Retrieved December 5, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ macOS 12 Monterey: The Ars Technica review. (October 25, 2021) Retrieved May 6, 2023 from Ars Technica

- ↑ macOS 13 Ventura: The Ars Technica review. (October 26, 2022) Retrieved May 6, 2023 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Template:Unbulleted list citebundle

- ↑ Apple Updates iWork, iMovie, GarageBand, Final Cut Pro And Logic Pro To Support macOS Big Sur And Apple M1 Macs. Oliver Haslam. (November 13, 2020) Retrieved May 6, 2023 from RedmondPie

- ↑ Template:Unbulleted list citebundle

- ↑ Mac utility Homebrew finally gets native Apple Silicon and M1 support. Samuel Axon. (February 5, 2021) Retrieved December 8, 2022 from Ars Technica

- ↑ Introduction to Porting UNIX/Linux Applications to OS X. Apple. Retrieved November 12, 2022 from [1]

- ↑ The Xcode cliff: is Apple teaching kids to code, or just about code?. Paul Miller. (March 29, 2018) Retrieved October 4, 2022 from The Verge

- ↑ A closer look at macOS Ventura. (October 24, 2022) Retrieved October 26, 2022 from TechCrunch

- Pages with script errors

- Articles with short description

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Good articles

- Use mdy dates from November 2023

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles containing Japanese-language text

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from November 2023

- Pages with broken file links

- Commons link is locally defined

- Official website not in Wikidata

- Macintosh computers

- Computer-related introductions in 1984

- Macintosh platform

- Apple computers

- Steve Jobs