X-Directional Stability

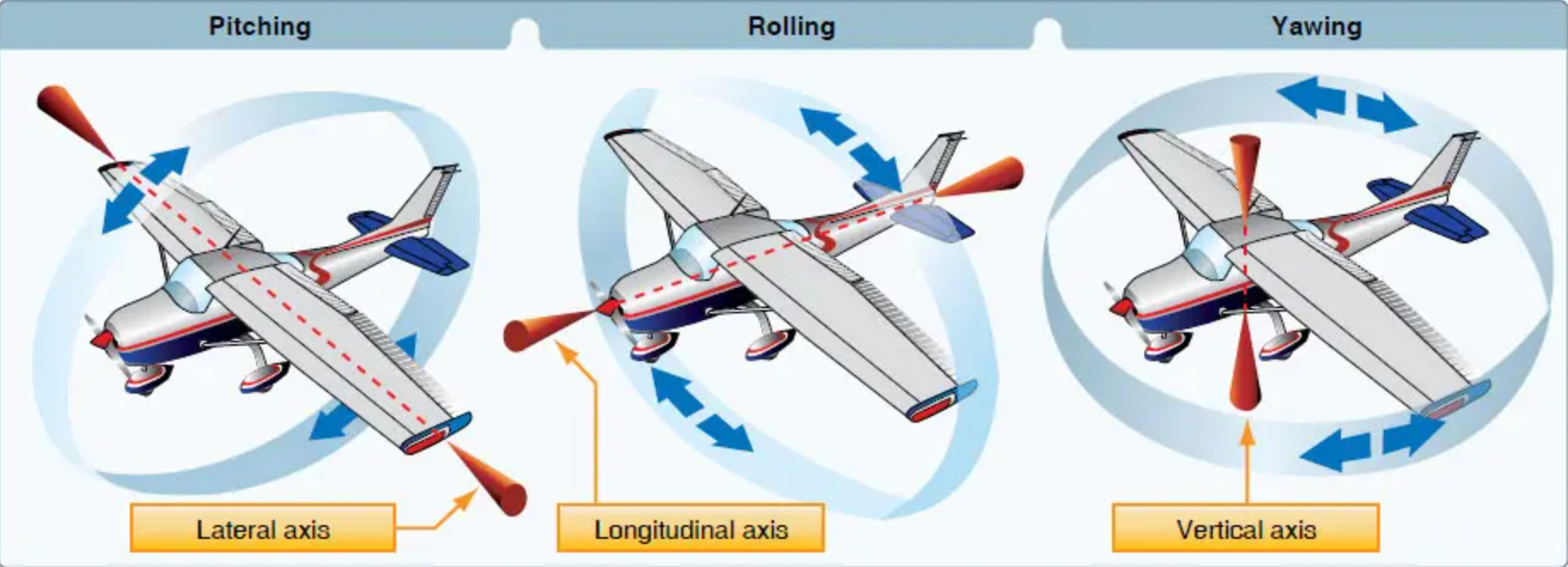

X-directional stability in aviation, also known as directional stability, refers to an aircraft's ability to maintain its intended direction of flight, resisting unwanted yaw (sideways movement) due to disturbances like wind gusts. It's essentially the aircraft's tendency to align itself with the relative wind, similar to a weather vane.

Elaboration

Definition

Directional stability is crucial for maintaining a straight and steady course, preventing the aircraft from deviating significantly from its intended path.[1]

How it works

Aircraft designers strive to create a shape and configuration that encourages the aircraft to "weathercock" into the wind, meaning it naturally rotates about its vertical axis (yaw) to point into the oncoming airflow.

Key components

The primary contributors to directional stability are:

- Vertical stabilizer (fin): This surface, positioned at the rear of the aircraft, provides the primary aerodynamic force that counteracts yaw disturbances.

- Fuselage shape: The shape and size of the fuselage can also contribute to directional stability, either positively or negatively.

- Engine nacelles or propellers: These elements can introduce destabilizing forces due to their aerodynamic characteristics.

Importance

Directional stability is essential for safe and controlled flight, especially during maneuvers or in turbulent conditions.

History

The understanding of directional stability and its design principles has evolved alongside the development of aircraft. Early aircraft designs, like the Wright brothers' biplane, relied heavily on the rudder (a movable control surface on the vertical stabilizer) for both control and directional stability. As aircraft designs became more complex, designers developed more sophisticated ways to achieve stability, such as optimizing the size and shape of the vertical stabilizer and incorporating other aerodynamic features.